In France, Brittany is known for its menhirs from the Stone Age. However, menhirs are not only found there. In the mountains of Massiv Central numerous menhirs stand across the landscape. But the formations of menhirs in southern France look completely different from those in Brittany, which makes the original purpose of these stones particularly mysterious.

The Massif Central stretches across the south of France, covering almost a quarter of the country's area. The south-eastern part of the Massif Central is called the Cévennes. The area is popular with tourists and is characterised by plateaus and deep valleys. Industry has never taken root here, and the villages and small towns have retained their original character. The conditions for agriculture are also far from favourable: the soil is poor and the terrain mountainous. Some of the rivers have carved their way several hundred metres deep into the limestone and are bordered by steep rock faces. This makes the area difficult to access and cultivate. Some villages in the river valleys only gained road access in the 20th century and were previously accessible by flat-bottomed boats only.

The Massif Central stretches across the south of France, covering almost a quarter of the country's area. The south-eastern part of the Massif Central is called the Cévennes. The area is popular with tourists and is characterised by plateaus and deep valleys. Industry has never taken root here, and the villages and small towns have retained their original character. The conditions for agriculture are also far from favourable: the soil is poor and the terrain mountainous. Some of the rivers have carved their way several hundred metres deep into the limestone and are bordered by steep rock faces. This makes the area difficult to access and cultivate. Some villages in the river valleys only gained road access in the 20th century and were previously accessible by flat-bottomed boats only.

The Cévennes are therefore not the kind of place where farmers and cattle breeders would be likely to settle. So why are there several hundred menhirs in the Cévennes?

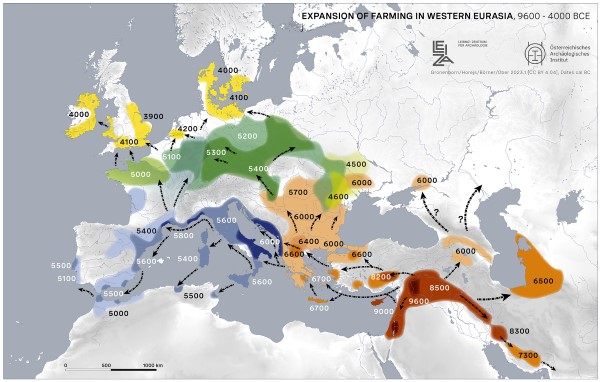

Historians believe that the menhirs were erected by our Stone Age ancestors, who brought agriculture and livestock breeding to Europe from the Near East. Through archaeological research and modern genetic methods, scientists have been able to determine how the culture of farmers and livestock breeders gradually spread across Europe from around 10,000 BC. This spread took place along the coastlines and along the river Danube, as shown in the adjacent illustration. Settlers appeared in the Cévennes region around 5,400 BC. Favourable conditions for agriculture and livestock breeding were probably not the reason why they settled there. So what drove them to this inhospitable area?

Historians believe that the menhirs were erected by our Stone Age ancestors, who brought agriculture and livestock breeding to Europe from the Near East. Through archaeological research and modern genetic methods, scientists have been able to determine how the culture of farmers and livestock breeders gradually spread across Europe from around 10,000 BC. This spread took place along the coastlines and along the river Danube, as shown in the adjacent illustration. Settlers appeared in the Cévennes region around 5,400 BC. Favourable conditions for agriculture and livestock breeding were probably not the reason why they settled there. So what drove them to this inhospitable area?

Perhaps the menhirs can give us a clue as to what the early settlers were doing in this area. What can be deduced from the arrangement of the menhirs in the Cévennes?

While the menhirs in Brittany usually stand alone or form long rows of stones as in Carnac, the menhirs in the Cévennes are often arranged in small groups. Such groups consist, for example, of two closely neighbouring stones and other menhirs arranged a few dozen metres away. Sometimes several menhirs form a rough line, with distances of several dozen metres between them. The menhirs of the Cévennes are neither particularly large nor particularly small, typically rising 1 m to 2.50 m above the ground. Although there are several hundred menhirs in the Cévennes, they are not particularly noticeable in the landscape. They are usually not located at prominent points in the landscape, but are often hidden on slopes.

Historians still do not know for what purpose the menhirs were once erected. The standard hypotheses can be ruled out: Usage as a stone calendar, as is assumed for stone circles, is implausible because the stones are not aligned with the seasonal course of the sun. Furthermore, it would not have been necessary to erect several of these structures only a few kilometres apart. The same is true for ceremonial places. The menhirs cannot be burial sites either, as no bones or grave goods have been found near them. Nor can the stones have served as waymarks, as a more visible and strictly linear arrangement in the landscape would have been chosen for this purpose. There are no recurring formations with similar patterns; each formation appears to be unique. It seems most likely that the stones establish a small-scale relationship to each other, which extends over a few dozen to a few hundred metres. What could have been marked with these stones?

Historians still do not know for what purpose the menhirs were once erected. The standard hypotheses can be ruled out: Usage as a stone calendar, as is assumed for stone circles, is implausible because the stones are not aligned with the seasonal course of the sun. Furthermore, it would not have been necessary to erect several of these structures only a few kilometres apart. The same is true for ceremonial places. The menhirs cannot be burial sites either, as no bones or grave goods have been found near them. Nor can the stones have served as waymarks, as a more visible and strictly linear arrangement in the landscape would have been chosen for this purpose. There are no recurring formations with similar patterns; each formation appears to be unique. It seems most likely that the stones establish a small-scale relationship to each other, which extends over a few dozen to a few hundred metres. What could have been marked with these stones?

Looking down at the ground, I found a possible answer to the riddle: There were brown-coloured pieces of heavy rock that clearly differed from the limestone of the gorges and the granite of the mountains. Ore! In fact, the area around Mont Lozère, where most of the menhirs are found, is known for its ore mining. There are deposits of iron, lead, zinc and silver, which have been proven to have been mined from at least Roman times until the 20th century. So did the early settlers perhaps move to the Cévennes because of the ore deposits close to the surface and therefore easy to mine, and did they stake their claims with stone menhirs?

This hypothesis easily explains why the menhirs are mainly found on slopes and do not form recurring patterns. Since the menhirs were erected to mark ore deposits close to the surface, the menhirs stand in irregular patterns somewhere in the landscape.

However, there is severe mismatch: The mining and processing of ores only began at the end of the Neolithic period with the transition to the Bronze and Iron Ages. If the menhirs actually served to mark the boundaries of ore mining areas, they would have to be younger than previously assumed. The beginning of the Bronze Age in Central Europe is dated to around 2,200 BC, and the beginning of the Iron Age to around 800 BC. However, there were probably isolated cases of metalworking earlier on, before it became widespread and metals replaced the stones that had been used to make tools and weapons until then, giving the Stone Age its name. In particular, the naturally occurring metals silver, gold and copper were also used by humans much earlier. So was it perhaps silver that attracted people to the Cévennes at an early stage?

Assessment

Strengths:The assumption that the menhirs served to mark claims in ore mining is original and has not yet been found in the literature.

Weaknesses:There is no direct evidence that ore mining actually took place in the vicinity of the menhirs. Geological investigations would have to be carried out to lend credibility to this hypothesis.

Comments powered by CComment